Why So'Bosch?

Thu 20th Feb 2020

What this essay says

I am captivated by the work of Hieronymus Bosch, so much so that making Bosch inspired ceramics and prints has been a major thread of my art practice for the last ten years. This essay is a meandering enquiry into my motivation for Boschesque making and into what my So’Bosch work means to me. I will wander between the personal and the general, between certainty and reticence. And, inevitably, I will consider why I am compelled to make art at all.

Why I Started making Bosch inspired Ceramics

Initial inspiration came to me while standing in front of Hieronymus Bosch’s large triptych, The Garden of Earthly Delights, in the Prado, Madrid. Right there I was gripped with the desire to make ceramic versions of the things depicted in the central panel of the painting. I returned home and created the Red Tree-Branched Tepee. Since then I have continued to make ceramic objects from The Garden of Earthly Delights and other Bosch paintings. I also make prints as part of my exploration into Bosch’s work.

The Garden of Earthly Delights

The Garden of Earthly Delights is a triptych, Bosch’s favoured format for both sacred and secular commissions. To the righteous right of God is Paradise with Adam and Eve, while on the sinister left is hell and damnation. In the centre is a visual enigma, as it represents no known scene from the scripture. The Garden of Earthly Delights is considered Bosch’s most elusive work.

Bosch was a master of baffling oddities, and never more so than in The Garden of Earthly Delights. He was a capricious originator of wondrously strange beasts, semi-animated structures and conglomerate forms. He invented things fantastical and bizarre yet simultaneously plausible. Using prototypes from nature, but scaled up, mashed and transformed Bosch conjured up another reality for our delectation.

The central panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights is busy, with many vignettes of human interaction. In the foreground there are acts of carnal desire but mostly just a lot of naked people lounging around in groups looking a bit vacant. Mid-ground there is a triumphant parade of animals and men around a lake, and in the distance a collection of very odd vertiginous pink and blue structures.

Many describe Bosch’s mixed up scale, organic exuberances and transmogrified animals as fantastical or warped, as religious allegory run amok and the imaginings of a madman. But that is an interpretation from the perspective of current knowledge of the world and our understanding of natural phenomenon, the animal kingdom and contemporary faith and learning. And maybe it is an interpretation by those who have left their capacity for wonder and astonishment behind.

The Garden of Earthly Delights is my favourite of his paintings. It seems a joyous depiction of the fate of humanity in all its complexity. I find nothing strange or inconceivable about the depiction of animals, beings or forms. Isn’t life an intricate web of perceived realities? One person’s reasoned argument is another’s abominable contrivance. Even one person’s perception of the colour purple can be another’s blue.

The Garden Earthly Delights makes mischief of interpretation. Both past and present historians, scholars, artists, collectors, thinkers and others have theorised, plundered, plagiarised and fantasised as to its meaning and message. Many hate it, others are ambivalent, and some adore it. The Garden Of Earthly Delights is an extraordinary painting. I have become familiar with it as a consequence of my decision to make ceramics pieces inspired by objects and built forms found in the painting. I have read about Bosch, and in 2016 made the pilgrimage to s-Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands for the exhibition to mark Bosch’s 500th anniversary.

The Bosch paintings in the Prado Collection are more colourful and less focused on the satanic realm of hell than many of his works. The Prado collection consists of The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, Triptych Adoration of the Magi, The Stone Operation and The Hay Wain. I am not interested in Bosch’s depiction of hell, or the human figures in his paintings. What concern me are the pictorial dioramas Bosch creates and the things that occupy these painted scenes.

Many of the things I select to make are at the periphery of the paintings or are bit part players, with only incidental significance in the drama of human fate that the paintings depict. Many are quite ordinary things, chairs, tables, bagpipes and tents. Others are unknown structures such as the tors that litter the distant landscapes of Bosch’s paintings. Sometimes artifacts are simply themselves, a chair is but a chair. Other times they are enlarged and utilised for some strange function. Musical instruments become apparatus for torture, a nun’s wimple the roof of a building, mussel shells become human hidey-holes and strawberries as big as boulders abound. In my So’Bosch ceramics I too am removing, re-forming, re-arranging and re-purposing objects, Bosch’s objects, simply for the pleasure of these forms and their very thingness.

Bosch’s paintings seem to be telling us that the folly of the world cannot be sufficiently disdained and mocked. I don’t look on these paintings as factual, static, or as historical, to be analysed and understood implicitly. I view them as synonyms, offering up an alternative vision of all that is confusing about life and the world.

The Reveal

In modern museums the paintings are on open display, to be strolled past or studied according to the whim of the visitor. But paintings like The Garden of Earthly Delights, were intended to be hidden behind their triptych wings and were only seen on special occasions when the doors were opened to reveal an explosion of colour and wondrous imagery. It must have been as astonishing as first experience of a photograph, colour TV, views of earth from the moon, or virtual reality has been. All the triptychs, but especiallyThe Garden of Earthly Delights due to its unconventional central panel, present the viewer with a sudden profusion of imagery in a dazzle of colour and gilt.

Spatial structure of Bosch’s painting

Bosch’s paintings can be seen as ostentatiously unstructured, mutable, amorphous spaces or as rigidly structured and ordered, defined by lines, circles, breaks, and framings. Their composition is a complex spatial illusion constrained within pictorial rules of the late medieval period. There are multiple vanishing points and the placement and scale contradict linear perspective. With no centralized gazing point the eye dashes hither and thither across the picture plain, attempting to circumnavigate the whole; sometimes in search of the very subject of the painting, other times to comprehend the riotous imagery and take in the multitude of allegories.

Bosch painted emotive landscapes that invite entry; they are both scary and tantalizing. I find pleasure in the unusual, conglomerate somewhat amorphous inanimate objects that clutter a Bosch landscape. Particularly the tor like structures that resemble or combine rocks with sea creatures, musical instruments, weaponry, astrolabes, and vegetal matter. My prints explore Bosch’s use of a high horizon line with little sky above and the placement of structures within the landscape.

Meandering thoughts and conflations of ideas

I often feel disjointed from the adult world, a similar feeling that Bosch’s paintings provoke, as his paintings are quandaries not absolutes. The message that viewers find when looking at Bosch’s paintings is distinctly ungraspable, and in particular The Garden of Earthly Delights makes people feel uncomfortable. I am utilizing Bosch’s language and extending it into 3D to create a world, a So’Boschscape, that makes others feel as discombobulated as me.

The thingness of things

Some things have more thingness than other things. Artefact, such and such, curio, objects, pieces, tchotchkes, trinkets, piffle, ephemera, doodahs, stuff, effects and items unspecified. Objects are the symbols by which we present ourselves to the world. Many objects have use, value and an exchange value; they are material goods and belongings. Other objects are more thing like; they are superfluous and have no functional use, rhyme or reason. I like things, and I like making things, as anyone who knows me or who has been to my house will testify.

Many of us have ornamental knick-knacks artfully displayed in our houses. They are retainers and deposits of memories, with individual meaning and stories of acquisition, gift or creation. The act of inventing and crafting artifacts is essentially human. Craft is an interesting word as its multiple meanings are almost adjectives for Bosch’s paintings; skill and proficiency in doing or making something, deceptive, having guile, and a boat, ship, aircraft or spaceship. Bosch’s Ship of Fools, flying fish and strange protrusions in the landscape foretell of sky crafts of the future. Look up the synonyms and antonyms of craft and you get, amongst others; conceive, concoct, devise, assemble, reframe, shape, author, write and express.

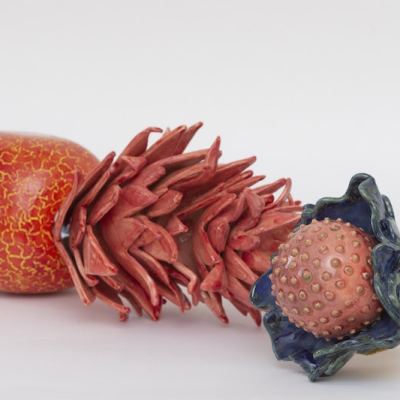

My So’Bosch pieces reference and pay homage to Bosch, but I am creating my own work, not attempting an actualisation or illustration of Bosch but a personal interpretation. I always know what I am going to make next, and I abandon the source material once in the pottery studio. The discrepancies between the original and the object that I make are curious. What I remember and focused on, or what I forgot or never noticed is intriguing. In isolating objects from their original position in Bosch’s paintings I am emphasising their thingness and making them into individual objects, creating a new thing from a Boschesque no-thing.

English Conversation Pieces

The genre of painting known as Conversational Pieces depict informal group portraits; family and friends apparently engaged in genteel conversation. The phrase ‘conversation pieces’ later acquired a different meaning in the English language. It came to mean an object of sufficient interest to start a conversation. Objects, often items related to science and scholarship, were placed in view to act as props for conversational openings.

My So’Bosch colourful glazed ceramic oddities are conversation pieces. They are attractive, strange and unusual objects that start people talking. Placed in relationship to one another they form a So’Boschscape of things that are also in dialogue with each other. Weirdly the So’Boschscape looks strangely like my favourite TV programme, The Magic Roundabout.

Dolls houses

I have always made things and environments. As a child I played endlessly with a dolls house that was laid out on top of a long built-in bedroom cupboard. For me it was always about the creation of spaces, and the placement of the pieces of furniture and knickknacks more than the dolls. Dolls were only present as supporting cast in the long running re-design of their living quarters. It was interior decoration gone mad. I curated the space and the placement of the everyday; from miniature furniture to the made, the found, the acquired, the re-appropriated and the superfluous. This play space was my world; it was safe and unchallenging compared to the real world of words I could not read and numbers I could not make calculate. In retrospect I realise this was the starting point of me being an artist. There may be more elevated subjects for art than creating little worlds and playing with the placement of small things but I am never happier than when making colourful objects and displaying them.

Cabinet of curiosities

This cupboard top dolls house was my Cabinet of Curiosity. Domestic in theme and diminutive in scale, it was my place to display treasured things. Precursors to museums, Wunder Kammers - Wonder Cabinets or Cabinets of Curiosity were gathering places for rarities and anomalies from the natural world, both real and fabricated. Creators of Wunder Kammers collected, ordered, arranged, examined, explained, theorised and reasoned. These collections were foundation of scientific thought and research.

As an artist I constantly explore ideas by looking, reading, researching, writing and, most importantly, making. By forming my thoughts into tangible objects I make them concrete and graspable. With the So’Bosch ceramic I have turned my whole house into a Cabinet of Curiosities, surrounding myself with things to help me navigate the world.

So’Boschscape – caves, tents, shelters

After I had been making So’Bosch ceramic pieces for a number of years I realised that most of the things I was drawn to make were shelters of some kind.

On the realisation that the things I was most drawn to make from Bosch’s paintings that were tents, caves and enclosures, I wondered why? What is attracting me to spaces one can hide in, make believe and inhabit?

As a child I spent hours constructing and occupying play tents and sitting under tables. My parents were architects with their office in the home so there where lots of tables to hide under. In these play spaces I was within, yet separate from, the adult realm. Selecting to be seen and engaged with, or remain concealed and secret. Inhabiting these spaces I would construct things and draw on found scraps of paper. Seeing only legs and feet, and hearing snippets rather than whole, I lived within my head, engaged in an internal dialogue, and completely in a world of my imagination and making.

So again like the curatorial play in my dolls house a habit of childhood is manifest in my adult art practice.

Ideas of home, the domestic and the everyday permeate my work. I’m heavily influenced by my parents writing and design work around space, place, and the art of habitation. I am interested in how one reads a space, navigates around it, and finds a place for oneself in it. I am motivated to make and play with placement and display of objects within an existing area.

Metaphor and alchemy - one thing for another

In my research about Bosch, I read that he used funnels, furnaces and distilleries as metaphors for the Houses in which the science of alchemy and chemical transmutation occurs. Burgeoning sciences in the fifteenth century came into conflict with Christian belief and power but with some clever theology and semantics scientific exploration could be used as empirical proof. Analogies were made between the birth of Christ and the transmuting agent, the elixir of life; if miraculous virginal birth could come into being then never ending life is also possible. Much of Bosch’s work is believed to be about God’s enmity towards humankind since the expulsion from Eden and the fall into sin.

Using one thing to represent another is common in all art forms. Unconsciously at first, my So’Bosch work is using Bosch imagery to infer a personal mean. I make sense of my place via the act of making, interpretation via visual manifestation.

The four basic steps of Alchemy’s could inexplicably be instruction for creating my So’Bosch ceramics:

1. Conjunction: ingredients are brought together for mixing.

2. Slow cook: mixing of elements into an undifferentiated mushy mass

3. Putrefaction: substances are burned and cleansed to make whole again

4. Transmuted: the now clean ingredience are resurrected into final joyous form that can be presented to the public.

Stories, fables, myths

I am interested in the universality of fables, myths, legends, stories and religious allegories and their continued function in our cultural psychology. Bosch’s paintings reflect the religious beliefs and politics of his time. They are concerned with folly of man; sin, eternal damnation and the difficulty of maintaining one’s way along the straight and narrow path in a world filled with material distractions and whirlpools of enmity. What attracts me to his work is what I can say about my time using Bosch as the portal. Little has changed, minus of the Christian rhetoric and fear of Hell. Life is still a long, hard path to tread. It is confusing and complicated; bigotry, inequality and misogyny prevail. Arrogance, greed for wealth and material goods, wars, and the pillage of the environment seem uncontrollable.

Current political, social, and cultural issues leave me scratching for an understanding, a position and correct reaction. It is this state of muddle that makes me make things. I think through my hands and am trying to find my way. I think art is a kind of trickery that can bring about new understanding and revelation to both the maker and an audience.

What’s my conclusion?

Why Bosch?

First came the sudden desire to make the red tree-branched tepee, then the impetuous decision to create a horde of objects from Bosch’s paintings. I had no knowledge or thought beyond the doing with my hands as I love objects and I love making. Then came the question, why?

I find stimulus in the work of other artists, in artifacts in museums, in buildings, places, nature and the ordinary everyday. Ideas pop into my head and cross-pollinate and I follow them wherever they lead. And at the moment one of main paths of interest is Hieronymus Bosch. To imitate, copy, or plagiarise another artist is not good, but I believe I am maintaining my own voice whist taking inspiration and referencing Bosch.

Why this essay?

My reasons for writing are twofold. Firstly, it helps to bring clarity to an idea. Having to think and assemble thoughts into largish chunks of text makes me focus. In a way, writing and its accompanied research have become a means of home-critique in place of the art school crits. Having to think about why one makes raises and answers questions around the work, and informs the process.

The second reason for writing is because I get tongue-tied when quizzed about what I am making and why. Reading, researching and writing around my subject brings a degree of lucidity, which I can then more comfortably verbalise. I still feel uncomfortable talking about my work and regularly perform the artist’s squirm dance, but I am working on it.