Mixed Emotion

Mon 5th May 2025

Early in 2025 there was a call-out for contributions for a cloth book of sewn pieces, to be made in response to Mary Linwood’s (1755-1845) extraordinary embroidered paintings. On reading the ‘Stitching Emotions’ brief I immediately thought of Samplers.

A Sampler is a practice piece, a small rectangle of fabric worked in various stitches, line after line, stitch after stitch. It is a learning tool and a way of displaying the skills of the maker. Typically a sampler contains the alphabet and/or a short text; a homely motto or biblical quote and sometimes the name of maker and date it was produced. Plus, repeated rows of patterning; spiralling hoops, interlocking lines, dots, triangles, short bars of recurring shapes for future use in edging a fancy collar or cuffs. The alphabet is learnt for name tagging garments and home linen.

A ‘sample’ is also a small example of something; thread or fabric samples are common in the haberdashery trade. A sample is required to see exactly the colour, tone, feel, weight and texture of a piece of fabric or yarn before embarking on a sewing project.

Sewing is the act of stitching and suturing. A process of melding two things together, fabric pieces to make a garment or skin to fix a wound. Needles and thread are used to create something new and to repair damage, securely, decoratively, purposefully.

The sewing of Samplers was designed to keep women in their place, restrained within the home, contained, silent, demure. Sampler sewing was part of the relentless trap of domestic tasks imposed on female children.

However, an activity designed to keep young minds, hands and tongue at bay also became a means to undermine patriarchal authority. Silent sewing gives the stitcher time to think and to ruminate, and when thoughts run amok imagination is freed. Some women began using needles as their weapons, their chosen imagery became a secret truth-telling.

The result was needlework, embroideries, quilts and samplers that were sewn with dissent and subterfuge. No mere pleasurable frippery, repeat patterns are shorthand, coded messages of the up and down, zigzag of the everyday. Shapes, scribblings, doodles, marks holding meaning for the maker.

“……. Although I’ve kept a diary for the subsequent forty years, I’ve never recorded anything much beyond events. From the start, I used a line or a shape as a way of noting something without having to say it. In 1980, there’s a day covered in triangles and I know exactly what that was about. There are abstract lines on most pages, cutting across days was a clear indication of a mood. The week of my eighteenth birthday is two loose spirals and the next four weeks of my last summer before leaving home are a flat continuous line. I’m doing nothing but waiting. In September, as I prepare to leave and have received poor results, the line sages. When I look at these diagrams, the feelings of that time comes back to me. Here’s a series of zigzags on the day I was asked to come home because my father was leaving. I still don’t have words for that.“

Lavinia Greenlaw, Some Answers without Questions

The domestic is seen as a small subject despite domesticity being a matter of life and death. Its occurrence in small rooms and its interior nature makes it quiet. Noise is contained within, shut-up-able both in space and volume. The ‘speaker’ made to comply and be docile, is ignorable, unlike noise made outside the house that can boom, be heard, be seen. Gendered spaces, gendered volume, gendered relevance, gendered voices. It is not that women are not heroic, or their actions not epic, it is that they are not seen as equal. Their work not of equal importance, not valued, witnessed, recorded, spoken of. Simply overlooked like a low inconvenient wall. But small acts speak volumes.

Sewing is still considered a nicety. A necessity for re-attaching a button or making a running repair. A useful skill but not a real talent. Not an art. Continuously undervalued as ‘women’s work’ in the broader art historical narrative, sewing is in fact a vital social and cultural historical record of ordinary lives and everyday objects on the home, and a highly skilful and expressive medium of art.

I love sewing, feel bereft when I don’t have a sewing project on the go. I can’t be idle, can’t not be doing something with my time, my hands, my mind.

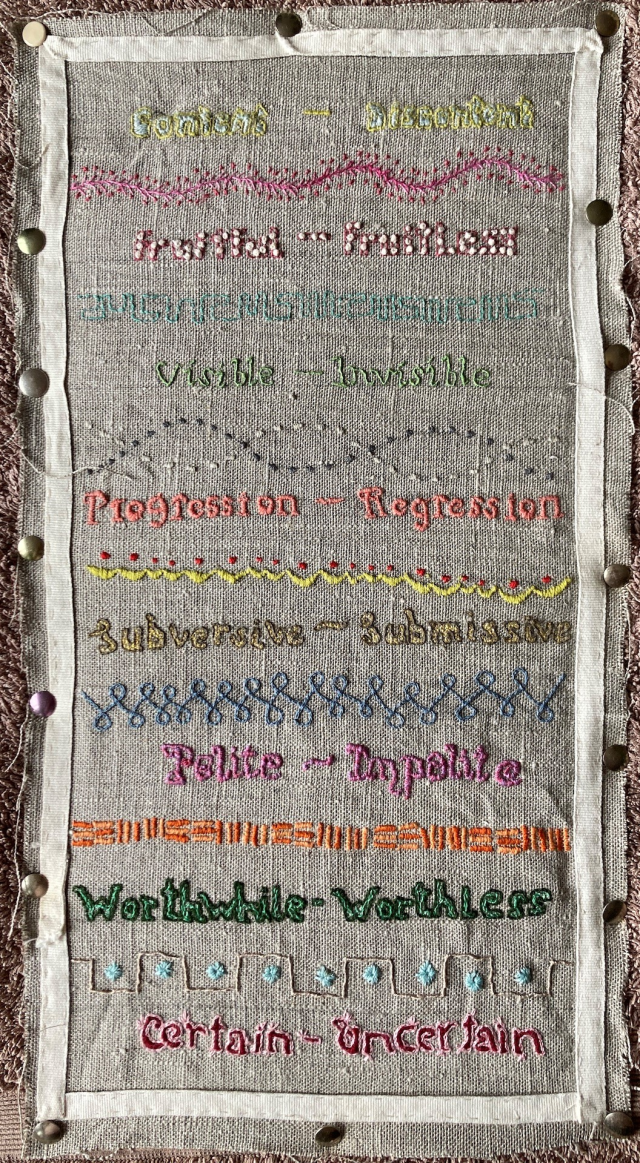

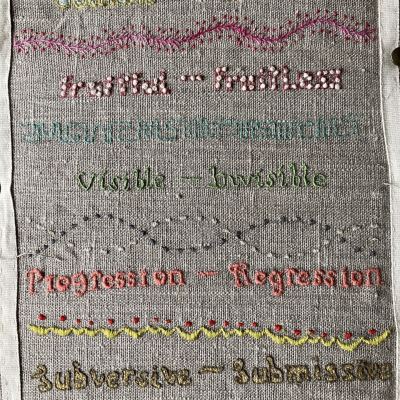

My sewing, as in other aspects of my life, is never perfect. I feel my output is always found wanting in neatness, straightness, spelling, accuracy. What I sew often ends up wonky, misaligned, mis-stitched, misspelt. I create meandering lines of thread and meaning which echo my personality. So, for me sewing throws up a mishmash of emotions from positive to negative, balanced on the ledge between failing and succeeding. For my contribution to the Mary Linwood fabric-book, I wanted to turn the Samples from from an instrument of oppression into a source of satisfaction, the ‘simple’ pastime into a language of opposition. The arrangement of eight lines of coupled words into a show of humorous resilience.

My Sampler expresses my mixed feelings about sewing. Feelings of being both subservient to sewing as a suitable gentile pastime, and being subversive in using sewing as a medium to express myself in alternative ways of being. Subverting the respectful act of running thread through fabric into an act of resistance against being silenced.

My Sampler is a mixture of triumph and rage.

Process: My Sampler is an embroidery worked in fine two strand silk and cotton thread on natural unbleached linen. Traditional Sampler’s are cross stitched and thus appear more pixelated.

The beauty of hand sewing on this scale is that it can be done anywhere. It is portable and doable in company, quietly working away whilst conversation or television watching occurs. Hand sewing or knitting physically appears and grows before one’s eye. There is instant gratification for time spent.

I started with the text, working my way down two words at a time. Then I reversed, working bottom to top, sewing the lines of patterns in-between the word pairs. The word pairs show a range of emotions; personalities almost. They are not all opposites, like Worthwhile and Worthless. Some are more oppositional but are relatable for me with my dyslexic befuddlement at language.

They display a range of emotions both positive and negative. My choice of words are linguistic contradictions which together form a kind of manifesto, or Eight Commandments, to be nailed to the wall. This represents the dual voices that are in my head; positivity to dejection, good side - naughty side.

Mis-construed language, women’s negative internal voices, and invisibility are all themes that recur through my art practice. So, although this piece was made in response to Ruth Singer’s ‘Stitching Emotions’ Call-Out, what I created is about me, and my personal, emotional relationship with sewing.

---------------*---------------

Mary Linwood (B. Birmingham 1755 - D. Leicester 1845) is one of the most notable needle-painter of eighteenth and nineteenth century alongside Mary Delany, Many Knowles and Eliza Morritt.

Mary Linwood began making embroidered pictures aged 13 and by 20 was established as a needlework artist. Linwood’s stitching was not created as part of domestic duties, or as paid work, or a pleasurable pastime. It was created as art by an artist.

For nearly seventy-five years, she worked in worsted embroidery, producing over 100 pictures. Linwood specialised in making full size copies of old masters, including paintings by Guido Reni, Carlo Dolci, Opie Morland, Jacob van Ruisdael and contemporises such as Thomas Gainsborough, George Stubbs and Joshua Reynolds. Linwood also produced needle-painted portraits of subjects including Lady Jane Grey and Napoleon.

Her needle-paintings are alternatively listed as Berlin Wool Work or Needlepoint. Linwood’s intricate sloping long and short stitches resembles brushwork. Linwood worked on coarse linen tammy cloth sourced in Leicester, using specially dyed crewel or worsted wool, with silk for highlights.

In 1786 Linwood was awarded a Silver Medal from the Society of Arts for her contribution to the arts. She also gained the attention of Queen Charlotte, Empress Catherine of Russia and, later, Napoleon who gave her the Freedom of Paris Award in 1803.

Respected and celebrated in her lifetime for her unique sewn paintings, upon death she fell out of favour. She and her work were forgotten and relegated to curious women’s craft. Her work is now being extracted from museum storage, revaluated and gaining long overdue appreciation.

Image and details:

Mary Linwood - King Lear after Sir Joshua Reynolds c.1785. Linen and wool with Silk Highlights